Blog

Sniffing My Neighbour's Phone Number

Please exercise caution and respect privacy laws when attempting to obtain personal information through unconventional means; this content is for educational and demonstrative purposes only.

In the midst of an otherwise ordinary afternoon, as I walked towards the university for a much anticipated lecture, I paused to browse the virtual corridors of X. Among the usual digital chatter, a particular post from LaurieWired surfaced as a warning to anyone who engages with technology without understanding its risks. LaurieWired is well known for expertise in digital security, and this time the message carried unsettling implications. The post highlighted vulnerabilities in AirDrop’s protocol, specifically how it omits cryptographic salts, making it susceptible to rainbow table attacks that could potentially reveal a user’s identity.

@LaurieWired’s tweet on X (formerly Twitter)

@LaurieWired’s tweet on X (formerly Twitter)

LaurieWired explained the process in clear terms. AirDrop broadcasts a Bluetooth advertisement without strong cryptographic safeguards and includes within it a partial hash of the sender’s phone number and email address. This hash allows a receiving device to recognize and authenticate the sender. However, because the hash is not salted, SHA256 hashes of phone numbers can be precomputed and stored in a rainbow table that is surprisingly compact, only a few terabytes in size. These tables can then be used to reverse engineer the hash back into the original phone number or email address. LaurieWired ended with a sobering note that currently there is no known method to fully prevent this information leakage, and countries such as China may already be exploiting this weakness.

This warning was more than a casual observation. It was a call to pay attention to how our data is handled and a prompt to explore how we can strengthen our digital privacy. In this blog post, we will examine this vulnerability, consider its implications, and reflect on the ethics of digital privacy in a world where technology advances more quickly than its safeguards.

Conducting Further Research on AirDrop Security

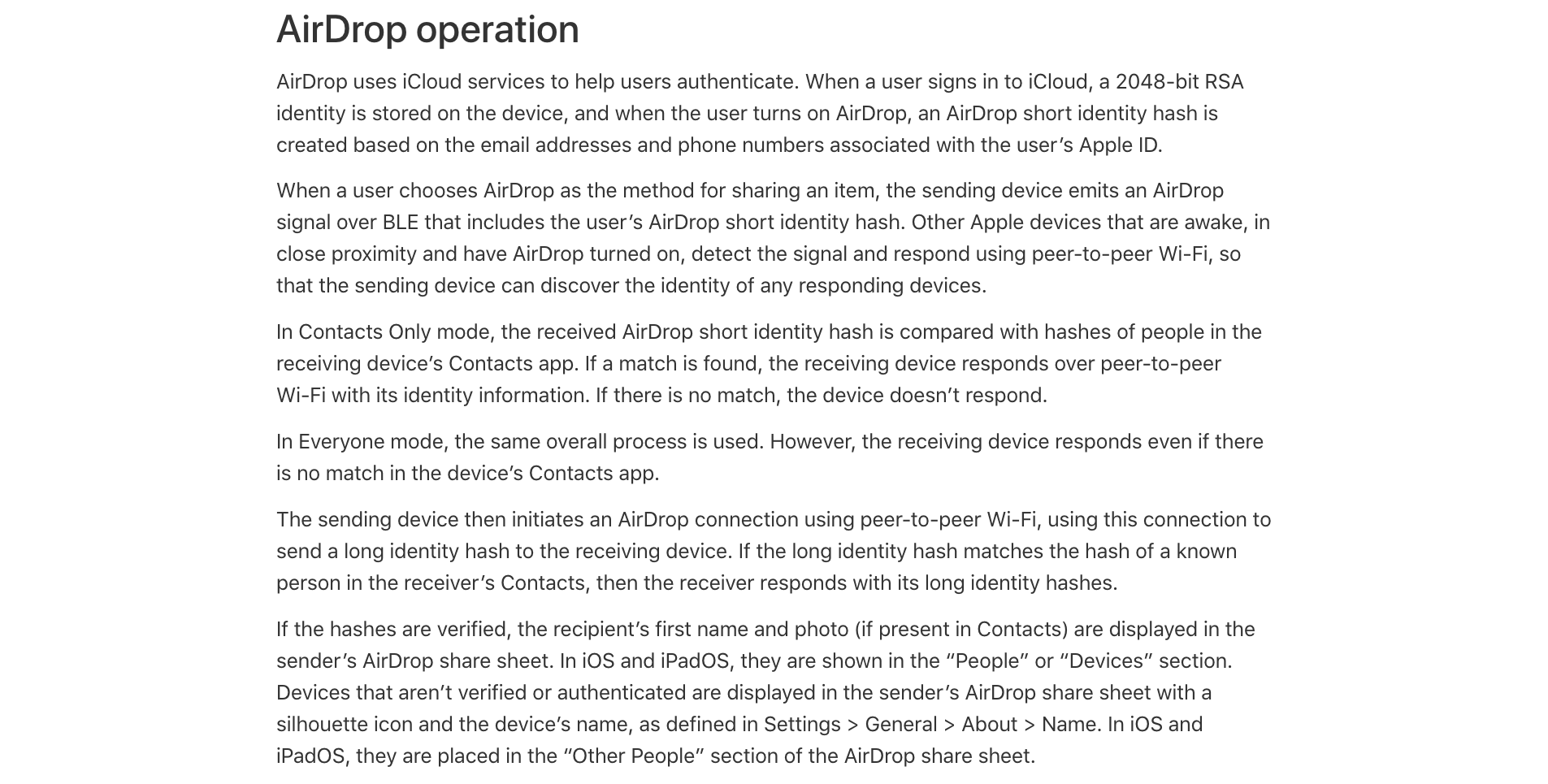

After absorbing the insights from LaurieWired, my curiosity grew. Once I returned home, I began searching for authoritative information and turned to Apple’s official documentation. Within their support pages, I found a detailed explanation of AirDrop’s security protocol that appeared more complex and secure than the description in LaurieWired’s post.

According to Apple, AirDrop uses iCloud services to authenticate users. A user’s link to their iCloud account is secured through a 2048 bit RSA identity stored on the device upon signing in. This cryptographic identity forms the basis for creating an AirDrop short identity hash, which is derived from the user’s Apple ID email addresses and phone numbers.

Apple’s official description of AirDrop’s secure file transfer process

Apple’s official description of AirDrop’s secure file transfer process

The process involves a series of digital exchanges. When a user initiates an AirDrop transfer, the device broadcasts an encrypted Bluetooth Low Energy signal that contains the AirDrop short identity hash. Nearby devices with AirDrop enabled detect this signal and begin a private exchange over peer to peer Wi Fi. In Contacts Only mode, the receiving device compares the incoming hash with hashes of contacts stored on the device. A match prompts a response. No match results in silence.

In Everyone mode, the receiving device responds to all broadcasts, prioritizing accessibility over selectivity. After the initial exchange, the sender and receiver establish a connection over peer to peer Wi Fi, during which the sender transmits a long identity hash. This ensures that the receiver is a known contact by matching the long identity hashes.

Apple’s explanation suggests several layers of defense, from RSA identities to the matching of short and long identity hashes. Despite these protections, LaurieWired’s findings indicate a potential weakness. The lack of cryptographic salts means that AirDrop may still be vulnerable to rainbow table attacks. This contrast between Apple’s official description and the demonstrated vulnerability forms the basis of our investigation.

Sniffing Bluetooth Traffic

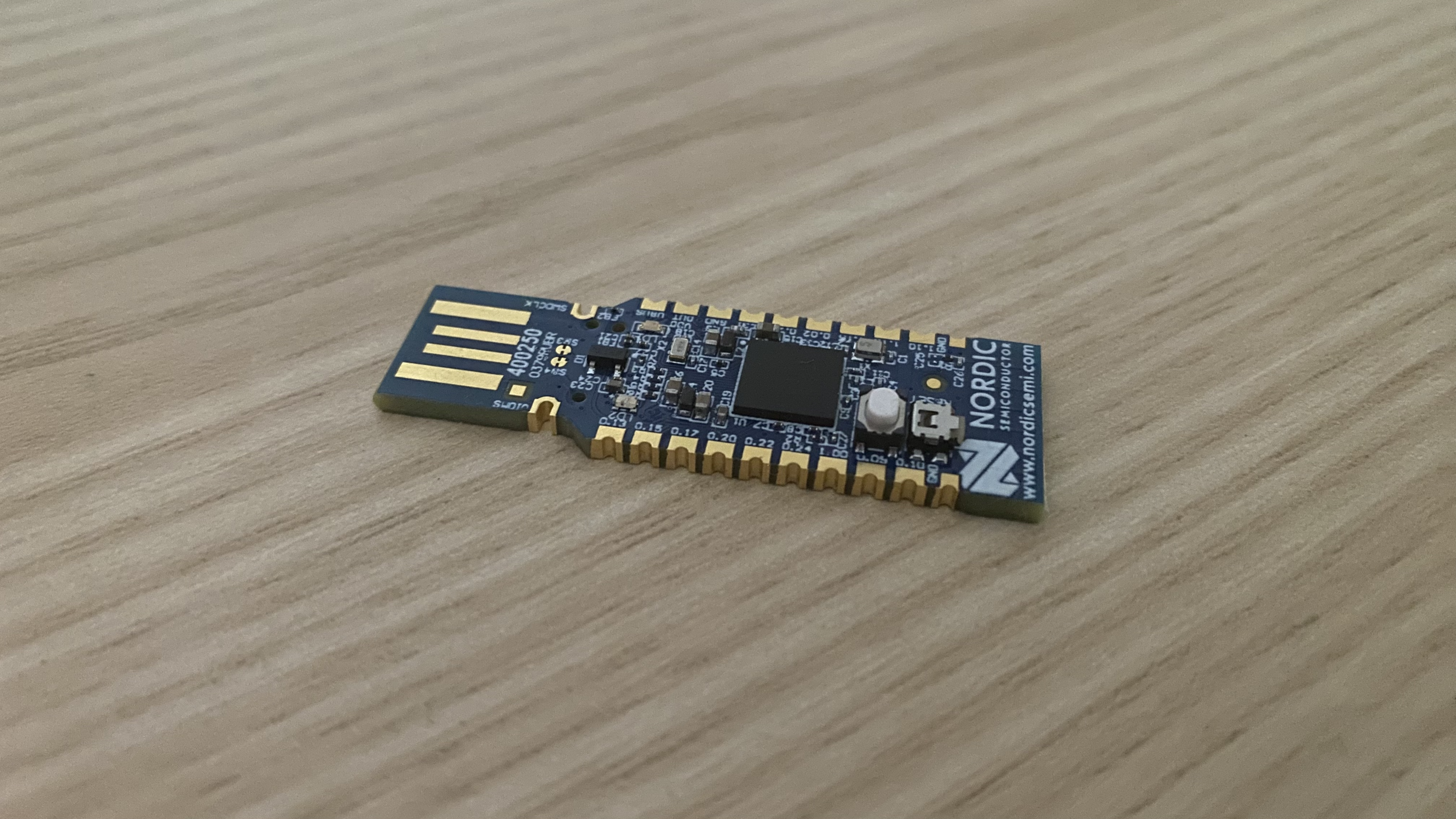

With the contrasting explanations from LaurieWired and Apple in mind, I conducted my own experiment to observe AirDrop’s behavior. For this, I used a Nordic Semiconductor nRF52840 Dongle, a compact and capable device for capturing Bluetooth traffic. Combined with Wireshark, a widely used protocol analyzer, this setup allowed me to observe the wireless signals in my environment.

The Nordic Semiconductor nRF52840 Dongle

The Nordic Semiconductor nRF52840 Dongle

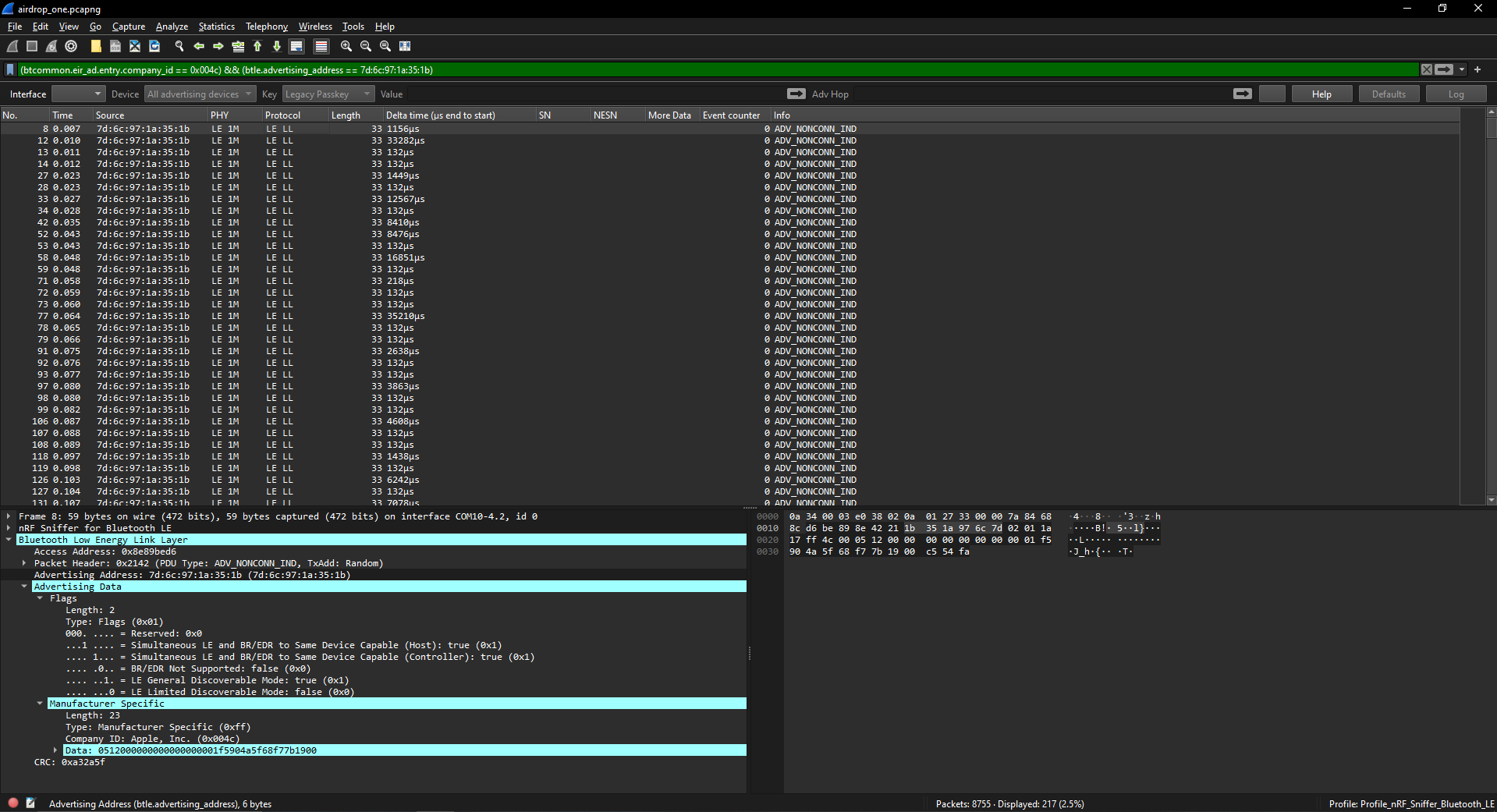

Once the dongle was configured and Wireshark was running, I began scanning for nearby Bluetooth activity. Before long, I detected a broadcast from a nearby Apple device. This was an AirDrop signal, and within its BLE packets was the AirDrop short identity hash that LaurieWired had described.

AirDrop’s broadcast data as seen on Wireshark

AirDrop’s broadcast data as seen on Wireshark

This string of hexadecimal characters, derived from an Apple user’s email and phone number, is intended to help devices recognize one another securely. Yet there it was, visible within the broadcast data and easily captured. The realization was significant. Anyone nearby with the right equipment and technical skills could intercept these broadcasts and obtain the short identity hashes.

The implications were clear. If these hashes can be reversed through rainbow table techniques, as suggested by LaurieWired, then personal information may be exposed more easily than expected.

Decoding the AirDrop Broadcast Data

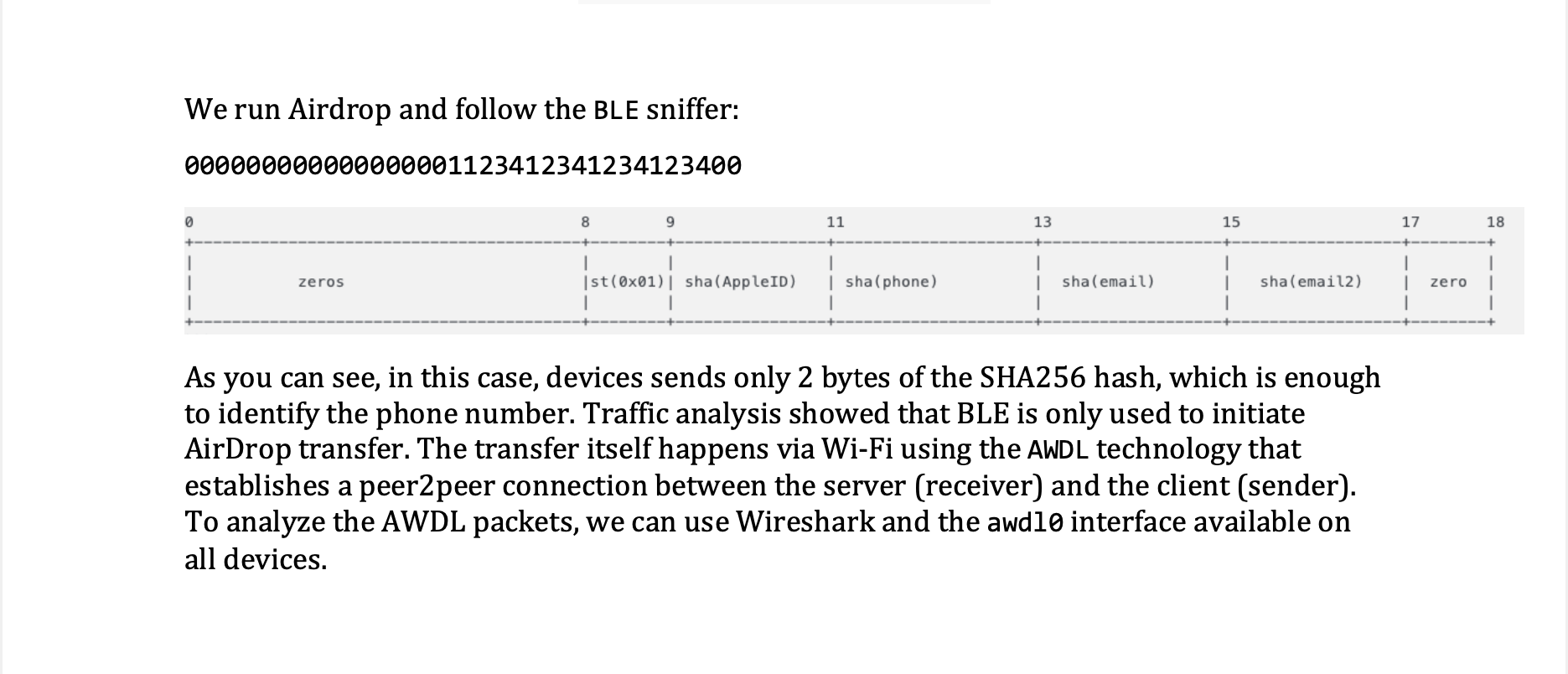

Motivated by the broadcast data I captured, which appeared as a 30 character hexadecimal string, I set out to determine which part of the string contained the partial hash. While searching for resources, I discovered a guide released by the team at Hexway that described this vulnerability in detail.

Hexway’s guide on the AirDrop broadcast data

Hexway’s guide on the AirDrop broadcast data

Hexway noted that during AirDrop communication, devices transmit only two bytes of the SHA256 hash of the user’s Apple ID, phone number, and email address. This was useful information. However, the broadcast data I captured differed in structure from Hexway’s examples. My data began with a preamble, 0512, followed by seventeen zeros before the string reached a sequence that matched Hexway’s format. I also observed that the partial hash in my capture was located near the end of the string, from characters 26 to 30, rather than positions 11 to 13 as described in the Hexway document.

Driven by curiosity, I wrote a Python script to generate partial SHA256 hashes for all phone numbers in Singapore. Singapore’s standardized numbering system made it feasible to compute these values for the entire range of numbers. In about thirty five minutes, the script completed this task.

The Redis database of partial hashes and phone numbers

The Redis database of partial hashes and phone numbers

To store the hash number pairs, I used Redis, a fast in memory key value data store. Redis was ideal for the task because of its high read and write speed and its support for persistence, which ensured the data would be preserved across restarts. Its simple key value structure made it perfect for quick lookups, which were necessary when identifying potential matches for each partial hash.

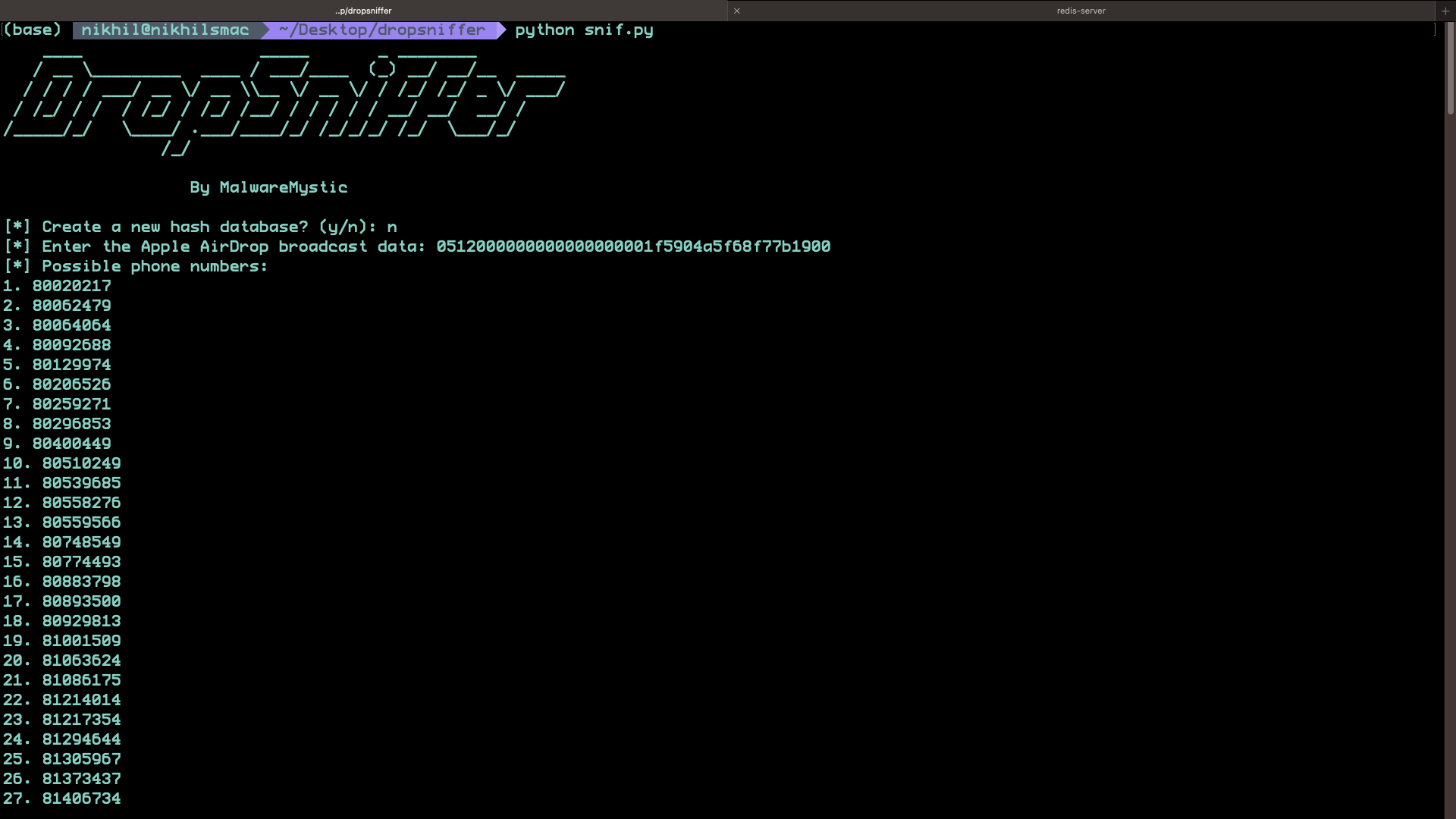

A list of all possible phone numbers

A list of all possible phone numbers

Because the hash fragment consists of only two bytes, collisions were expected. Many phone numbers will share the same truncated hash. When I compared the broadcast data against my Redis database, I found a list of nearly one hundred phone numbers that matched the partial hash. This was expected and served as a real demonstration of the limitations of using truncated hash fragments for security.

With additional information about active phone number ranges and targeted OSINT techniques, the list could be narrowed even further. This experiment illustrates that while AirDrop excels as a convenient file sharing tool, aspects of its design may expose users to unexpected privacy risks. A cautious and informed approach to its use is therefore essential.