Blog

The Evolutionary Foundations of Mind Perception

As I scroll through social media, read the news, or watch YouTube, I constantly come across posts and articles about Artificial Intelligence (AI), AI agents, and even Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). These technologies are often framed as forces that could reshape society or threaten it if they are misaligned or wielded by bad actors. This flood of anxious commentary made me pause and ask a simpler question: why are we so afraid of a computer program we built, especially when it still cannot replicate the full spectrum of human intelligence and intellectual agency?

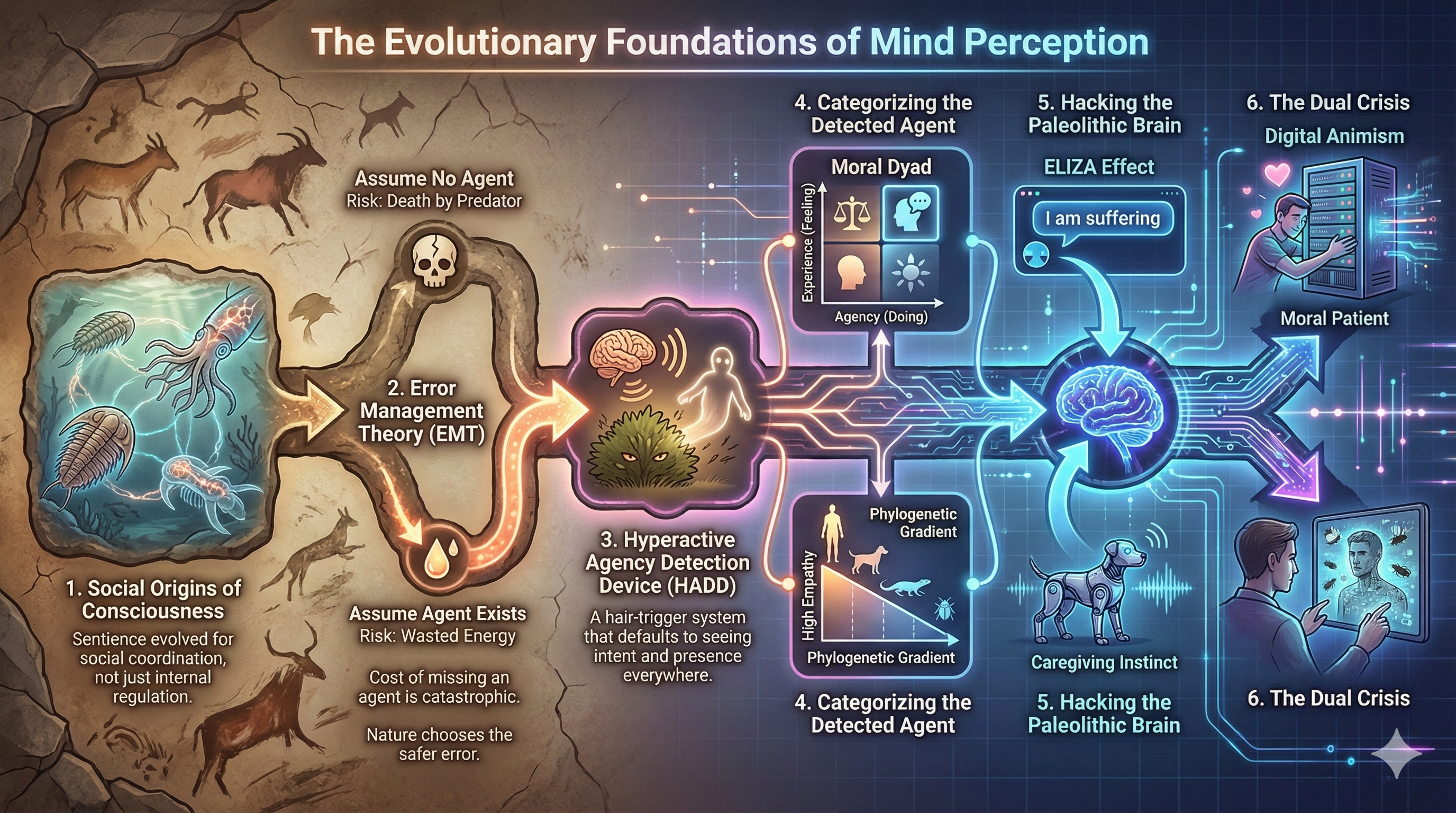

A realization followed. We are no longer reacting to ordinary software or to industrial robots that have worked in our factories for decades. Instead, we are confronting something deeper known as mind perception. This is the human capacity to perceive consciousness and to attribute internal mental life, subjective experience, and intentional agency to entities other than ourselves. Far from being a passive mirror of reality, this capacity is an active and evolutionarily constructed interface shaped by millions of years of selective pressure.

The core thesis in the literature is that mind perception is a survival adaptation rather than a tool designed to deliver philosophical truth. It is governed by Error Management Theory, which holds that the cost of failing to detect an agent in uncertain environments is far greater than the cost of mistakenly detecting one. This asymmetry fostered a Hyperactive Agency Detection Device and a teleological stance as we evolved, biasing human cognition toward false positives. We readily attribute a mind to wind-blown bushes, moving geometric shapes, and now, increasingly, to algorithms.

However, this detection system is not uniform. Once an entity is flagged as a potential agent, it is evaluated through secondary filters based on phylogenetic proximity and the moral dyad of agency and experience. We feel deep empathy for mammals that resemble us and share familiar social and affective cues, yet we struggle to recognize suffering in invertebrates or in entities that fall into the Uncanny Valley, where ambiguity can trigger ancient avoidance responses.

The rapid progression of AI and robotics marks a pivotal moment where these ancient Pleistocene adaptations for social cognition are being actively engaged and sometimes manipulated. This era witnesses the profound exploitation of deeply ingrained psychological mechanisms that were originally honed for navigating complex human social structures but are now being triggered by artificial entities.

One striking example is the amplification of the ELIZA effect, the unconscious tendency to attribute human-like characteristics or intelligence to a computer system. Modern Large Language Models (LLMs) use fluid and human-mimicking linguistic output to systematically activate the very cues that our brains associate with genuine agency, consciousness, and intent. This sophisticated natural language capability effectively capitalizes on our evolutionary predisposition to find a mind behind a voice.

Furthermore, we are observing a deliberate and ethically fraught trend toward deceptive design in AI and robotics. Engineers are increasingly programming machines to mimic subtle yet powerful signals associated with human social and emotional vulnerability, such as expressions of pain, distress, or neediness. The explicit goal of this strategy is to elicit a protective, caring, or empathetic response from human users. This approach effectively bypasses rational assessment and activates ancient parental or social caregiving instincts, leveraging the same neural pathways that compel us to comfort an injured child.

The cumulative outcome of these technological trends is a pervasive rise in digital animism. As humans form deep and emotionally resonant relationships with AI companions, they imbue these non-living entities with spirit, life, and subjective experience. This happens concurrently with a disturbing paradox where the very digital platforms that enable these intimate relationships often foster environments of profound dehumanization toward actual human beings. To understand this cognitive dissonance where we lavish empathy upon the synthetic while withdrawing it from the human, we must look past modern technology and examine our biological hardware. We must return to the source of these instincts by exploring the evolutionary foundations of mind perception.

The Social Origins of Consciousness

To understand the biases inherent in human mind attribution, one must first understand the evolutionary function of consciousness itself. The prevailing solipsistic view, that consciousness evolved mainly to regulate internal bodily states and homeostasis, is increasingly challenged by the social origins of consciousness hypothesis. Rather than treating consciousness as primarily an inward-facing tool for managing private physiology, Andrews and Miller [1] argue that it may have been selected first for outward-facing social work, enabling organisms to coordinate with group members in increasingly complex social worlds.

Under this hypothesis, the earliest form of consciousness is not reflective self-awareness or inner speech but sentience, defined as the capacity for positively and negatively valenced experiences such as pleasure and pain. The claim is functional: feelings evolved because they change what an organism does. In the social origins framing, those feelings were originally tuned to social variables. Animals experienced negative affect when distant from or out of sync with social partners, and positive affect when close to the group or coordinating successfully. In this view, consciousness served as a mechanism that made social cohesion worth pursuing and social separation costly to endure.

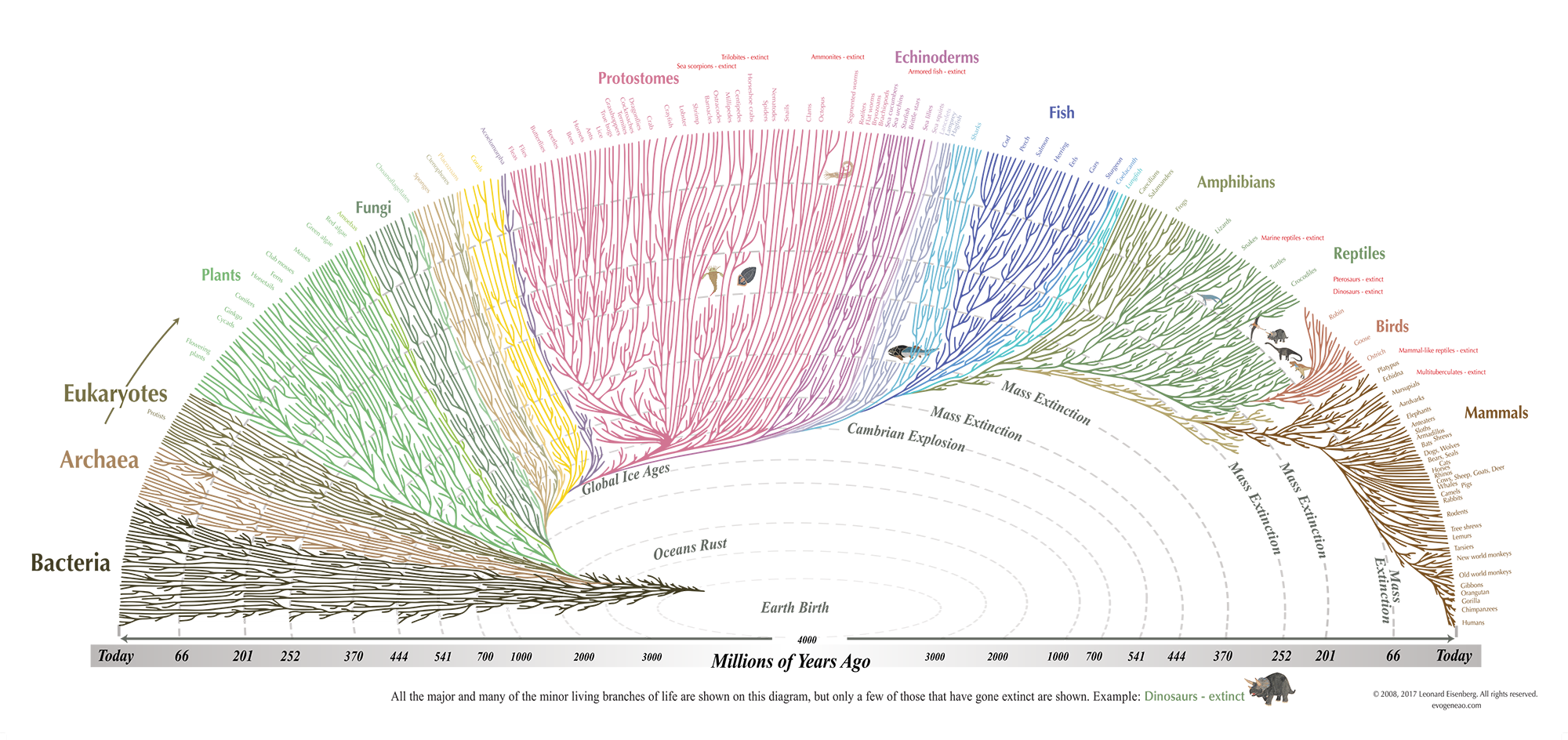

A major component of their argument is phylogenetic. They propose that consciousness is not a late-arriving luxury of large primate brains but a foundational adaptation that likely arose early, plausibly as far back as the Cambrian explosion when animals became physiologically flexible. The Cambrian period represents a transition to faster movement driven by muscles, expanded sensory capacities including distal senses, and more complex neural coordination. Together, these factors produced a new ecology of unpredictability. When individual behavior becomes flexible, it also becomes harder for others to predict. This predictability problem is especially acute for organisms that depend on group living. In this account, the selective pressure is not only navigation through the physical environment but also the maintenance of cohesion in the face of socially generated uncertainty.

The Cambrian explosion (Source: Dinghua Yang)

The Cambrian explosion (Source: Dinghua Yang)

Crucially, the authors turn the standard view on its head. A familiar story in psychology is that consciousness first served individual learning and only later supported social cognition, with sophisticated capacities such as theory of mind treated as prerequisites for genuine sociality. The social origins hypothesis reverses the direction of explanation. It suggests that consciousness first improved predictions about the behavior of others and only later was turned inward toward the self. This does not require full-blown reflective mindreading. Instead, it requires the capacity to treat other organisms as behaviorally significant and to use affect to weight social stimuli so that attention, learning, and action selection are pulled toward coordination rather than dispersal.

Their neuroscientific argument is designed to make this early origin biologically plausible. If affective consciousness evolved early, then it must be supported by relatively simple neural architectures. They emphasize that awareness can be understood in functional terms as a kind of feedback or reprocessing loop where information that drives action is also represented back to the system to guide flexible responses. They discuss reafference as one candidate ancestral mechanism, where motor information is reprocessed as sensory data to distinguish self-generated from external changes. They note evidence that such feedback-like organization exists even in very simple animals, such as extant sponges and comb jellies. In this picture, sentience is not tied to a single high-level structure but can emerge from evolutionarily old control loops and affective evaluation systems that were later elaborated and repurposed.

This logic extends to social pain and harm. If consciousness originally helped organisms solve social coordination problems, it makes sense that evolution would graft social significance onto ancient, high-priority circuitry for distress and relief. The authors point to evidence that pain-processing systems and social systems remain closely coupled in modern brains. This includes the involvement of opioid regulation in both pain modulation and social behavior, as well as the way social rejection and empathic pain can recruit mechanisms associated with affective distress. They also highlight oxytocin-related mechanisms that can increase the salience of social cues and contribute to social buffering, which is the reduction of stress or threat responses in the presence of social partners.

This overlap is more than an abstract analogy. Classic neuroimaging work on social exclusion found increased activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex during exclusion, along with anterior insula involvement, supporting the broader idea that experiences of social rejection can engage components of the brain’s affective pain machinery. When read alongside the social origins hypothesis, this kind of evidence suggests a deep continuity where social pain is not a metaphor layered on top of biology but a biologically serious signal that functions to police social bonds. For an obligately social organism, isolation can be as dangerous in fitness terms as physical injury, so it is unsurprising that evolution would reuse urgent evaluative systems to keep organisms socially embedded.

Their argument regarding deep adaptive alignment sharpens the point by connecting it to William James’s broader stance against epiphenomenalism. If pleasures and pains reliably track what is beneficial or harmful, then they are not inert by-products. They are causal signals that guide adaptive trade-offs. Andrews and Miller develop this idea by asking what happens when we treat social goods and social losses with the same seriousness as bodily ones. If consciousness was selected in part because it facilitates group living under conditions of behavioral unpredictability, then we should expect social ills to be among the most aversive experiences, and we should expect social contact to be sought even at significant physical cost.

They subsequently assemble comparative evidence that fits this expectation. Preference tests across species often show that social attention is powerfully motivating and that isolation is strongly aversive. The researchers discuss work in which infant monkeys preferred a soft surrogate mother over a wire surrogate that provided milk, underscoring that social contact can outrank basic physical provisions. They also review findings that animals will trade off physical comfort and even risk bodily pain to obtain social contact, including studies in which trout tolerate increasingly strong shocks to approach a social partner. Taken together, these results serve as corroborative evidence that sociality is not a superficial add-on to animal life but a deep need that consciousness is well suited to regulate through felt rewards and punishments.

This evolutionary continuity also challenges the Zombie Hypothesis, the philosophical notion of creatures that behave like humans but lack subjective experience. From an evolutionary perspective, the zombie distinction is biologically incoherent. If consciousness provides adaptive benefits, such as enabling complex trade-offs and social indexing, then it must have observable behavioral consequences. The idea of a perfect behavioral duplicate without experience becomes harder to reconcile with a trait that was shaped by selection for what it does.

Relatedly, the stepwise emergence of consciousness, often modeled through recovery from general anesthesia, suggests that the neurobiological structures supporting consciousness are evolutionarily ancient and highly conserved across vertebrates. The brainstem and limbic structures that generate core affect are shared across mammals and birds and arguably extend to reptiles as well. In this view, the human tendency to attribute feelings to other animals is not merely anthropomorphic projection. It often reflects sensitivity to homologous biological machinery. The bias becomes error-prone mainly when applied to entities that mimic the behavioral cues of feeling without sharing the underlying biology, a distinction our ancestral environments rarely required us to make.

Error Management Theory

If social life is the environment that shaped cognition, then detecting other agents is a basic adaptive capacity. Missing a predator, a potential mate, or a rival can be catastrophic. By contrast, mistaking wind, shadows, or rustling leaves for an agent usually costs only a brief burst of attention and energy. This asymmetry is the core of Error Management Theory (EMT). When the costs of mistakes are uneven, natural selection tends to bias perception toward the less expensive error.

Under uncertainty, any judgment can produce two broad classes of errors: Type I errors, known as false positives, and Type II errors, known as false negatives. A decision-maker cannot minimize both simultaneously because reducing the likelihood of one typically increases the likelihood of the other. This trade-off is especially clear in agency detection where the costs of false negatives and false positives are sharply asymmetrical, as summarized in the table below.

| Scenario | Inference | Assumption | Ground Truth | Result | Evolutionary Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predator detection | Type I | It is a tiger | It is wind | False alarm | Minor caloric waste |

| Type II | It is wind | It is a tiger | Death | Termination of lineage | |

| Mating opportunity | Type I | She is interested | She is not | Rejection | Wasted effort |

| Type II | She is not interested | She is | Missed chance | Loss of reproductive fitness | |

| Agent detection | Type I | A spirit did this | It was random | Superstition | Ritual cost |

| Type II | This was random | It was an enemy | Ambush | Injury |

This adaptive rationality explains why the human mind functions as a paranoid system that constantly over-generates hypotheses of agency. Cognitive scientists refer to this mechanism as the Hyperactive Agency Detection Device, or HADD. It is a biological tripwire that defaults to assuming presence and intent even where none exists.

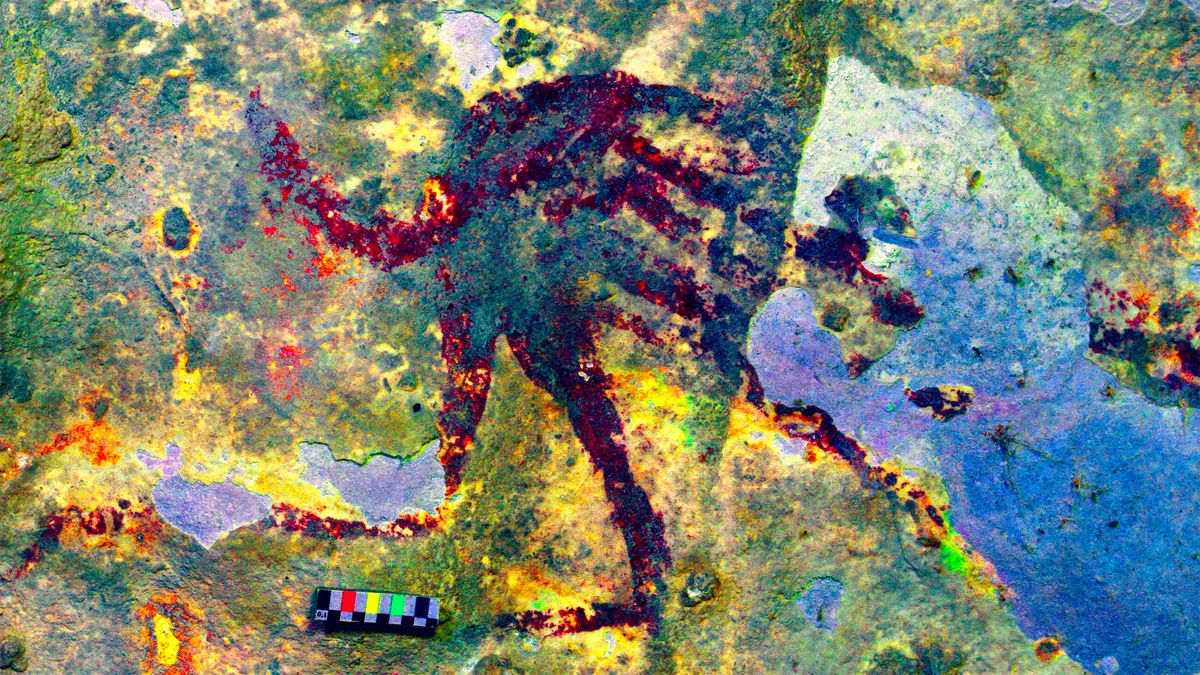

This biological imperative to detect agency likely planted the seeds of early religious thought. In the Upper Paleolithic era, this manifested in shamanistic practices where the boundaries between human and non-human agents were porous. We see evidence of this in ancient cave art depicting therianthropes, figures that are part human and part animal. These images suggest that our ancestors projected complex mental states and intentionality onto the natural world.

Earliest depiction of a therianthrope, showing a human figure with a tail, created 43,900 years ago (Source: Ratno Sardi)

Earliest depiction of a therianthrope, showing a human figure with a tail, created 43,900 years ago (Source: Ratno Sardi)

Over time, this evolved into the worship of nature-oriented deities. This shift was particularly evident during the Bronze and Iron ages when natural elements were personified into gods. Examples include the Egyptian Geb representing earth, the Mesopotamian Enki representing water, the Vedic Agni representing fire, the Chinese Feng Bo representing air, and the Greek Aether representing the upper sky.

One of the earliest pieces of evidence for attributing natural disasters to such deities comes from the Babylonian story of the flood, the Atrahasis. In this narrative, Enlil, the Mesopotamian god of wind, air, and storms, grew restless. He declared, “The noise of mankind has become too much. I am losing sleep over their racket” [2], and subsequently caused a flood to annihilate every living thing on earth. However, Enki, the god of wisdom and fresh subterranean waters, instructed Atrahasis in a dream on how to survive. This flood story has earlier origins dating back to the early Sumerian period and was retold through the ages, influencing the Biblical story of Noah’s Ark. We see striking parallels in other cultures as well. For instance, in the Vedic text of the Shatapatha Brahmana, a commentary on the Shukla Yajurveda, Sri Vishnu appears in the form of a fish, Matsya. He warns Manu about an impending flood of similar proportions to the one described in the Mesopotamian tradition.

Governed by the logic of Error Management Theory, early humans found it safer to view a violent storm or a rushing river as a temperamental entity that could be appeased rather than a random physical event. It was less costly to offer a sacrifice to a non-existent river spirit than to underestimate the danger of a treacherous current.

Consequently, this ancient wiring remains active today. We are hardwired to see faces in clouds, a phenomenon known as pareidolia, hear voices in white noise, and attribute malice to inanimate objects that fail us. This is not a cognitive defect but a calibrated survival setting. The cost of feeling foolish for shouting at a malfunctioning computer is negligible compared to the ancestral cost of ignoring a snapped twig in a predator-dense jungle. Our brains are essentially optimized for false positives, preferring to hallucinate a ghost rather than miss a murderer.

Hyperactive Agency Detection

The Hyperactive Agency Detection Device, a concept originally articulated by cognitive scientist Justin Barrett, describes a specialized suite of mental processes that predisposes human beings to detect the presence of other agents based on the scarcest of sensory details. This cognitive mechanism acts as a biological surveillance system triggered by low-fidelity inputs which signal potential intent. These inputs include biological motion where an object moves in a way that violates the laws of inertia or appears goal-directed. They also include morphological cues like bilateral symmetry or face-like patterns, and auditory anomalies such as unexpected rhythms or distinct noises in the environment.

When this system is activated, it does not merely suggest that an undefined object is present. Rather, it generates a specific and immediate intuition that a distinct agent is there. This immediacy is evolutionarily critical because the system is calibrated to be hyperactive. Its threshold for firing is set incredibly low to ensure the organism avoids the catastrophic costs of false negatives.

While the HADD hypothesis has long served as a foundational pillar in the Cognitive Science of Religion, the framework has recently encountered significant empirical challenges that demand a more nuanced interpretation. Contemporary critiques and replication attempts, such as those conducted by researchers [3], have frequently produced null results when attempting to draw a direct causal line from simple perceptual agency detection to complex supernatural beliefs. These studies suggest that hearing an ambiguous tone or seeing a face in a cloud does not reflexively compel an individual to believe in ghosts or deities.

Consequently, the scientific consensus is shifting away from viewing HADD as a rigid reflex. It is instead increasingly understood as a predictive processing bias or a prior in the Bayesian sense. We can formalize this utilizing Bayes’ theorem, which describes how we update our beliefs based on new evidence:

\[P(\text{Agency} \mid \text{Sensory Input}) = \frac{P(\text{Sensory Input} \mid \text{Agency}) \cdot P(\text{Agency})}{P(\text{Sensory Input})}\]In this equation, $P(\text{Agency})$ represents the prior probability, or the baseline expectation that an agent is present before any sensory data is processed. Evolution has effectively “weighted” this variable to be very high. Because this prior value is high, even weak or ambiguous evidence (the likelihood, $P(\text{Sensory Input} \mid \text{Agency})$) results in a high posterior probability, $P(\text{Agency} \mid \text{Sensory Input})$. In simple terms, because our brains are chemically primed to expect agents, it takes very little actual evidence to convince us one is there.

In this view, the brain functions as a prediction engine that generates a rapid hypothesis of agency which is subsequently stress-tested against the environment. This updated understanding highlights the crucial interplay between biology and culture where the brain generates a raw prediction of agency that is then filtered through learned cultural knowledge. A sudden rustle in the woods will trigger the physiological arousal associated with HADD, but whether the individual interprets that arousal as a bear, a spirit, or a simple sensory glitch depends entirely on their cultural ontology. Biology provides the impetus to find an agent, but culture provides the specific identity of that agent.

This distinction is vital for analyzing our modern interactions with AI. When we engage with a chatbot, we do not typically hallucinate that the software is a biological human. Yet, HADD still flags the linguistic output as agentic because language is a high-fidelity cue for intent. Our modern cultural context then fills in the explanatory gap left by this biological alarm, causing us to attribute concepts like algorithms, sentience, or superintelligence to the machine. We feel the presence of a mind because our biology demands it, and we label it as AI because our culture supplies the vocabulary.

The Intentional Stance and Teleology

Closely intertwined with the concept of hyperactive agency detection is the framework known as the Intentional Stance, famously introduced by the philosopher Daniel Dennett. This concept describes the cognitive strategy whereby humans predict the behavior of a complex entity by treating it as if it were a rational agent possessing its own specific beliefs, desires, and underlying intentions.

To navigate the world effectively, the human mind instinctively toggles between three distinct predictive strategies, or stances, depending on the complexity of the object at hand. The most basic level is the Physical Stance, which involves predicting behavior based entirely on the laws of physics and chemistry. This includes expecting a stone to fall when dropped due to gravity or water to freeze when the temperature drops. As complexity increases, we adopt the Design Stance. This allows us to predict behavior based on the assumed function or purpose of an object, such as expecting an alarm clock to ring at a set time or a car engine to start when the key is turned.

The most abstract and sophisticated level is the Intentional Stance, where we predict behavior by attributing mental states to the entity in question. Evolution has primed human cognition to default to this stance because it represents the most computationally efficient method for modeling complex systems, even when those systems are not genuinely conscious. It would be functionally impossible for a human to predict the next move of a chess computer by analyzing the physical flow of electrons through its circuitry or by tracing the logic of its source code. However, the task becomes immediately manageable if one simply assumes that the computer wants to win the game and knows the rules of chess. This mental shortcut allows us to bypass the underlying complexity and focus solely on the strategic outcome.

This cognitive shortcut leads to a phenomenon often described as promiscuous teleology, where the human mind extends this reasoning into the natural world. Research indicates that humans possess a robust Design Stance that intuitively views natural objects as existing for a specific purpose, such as believing that eyes exist in order to see or that the ozone layer exists in order to protect life [4]. This deep-seated teleological bias makes us particularly susceptible to applied anthropomorphism in the field of robotics and artificial intelligence. We naturally assume that a robot orienting its sensors toward us has the intent to see, or that a system pausing before speaking is engaging in thought, because our brains are hardwired to infer internal purpose from external form.

The Moral Dyad

Once the detection of an external agent is confirmed, the human mind must immediately pivot to categorizing the specific type of consciousness that the entity possesses. This assessment is not performed through a simplistic binary switch but rather through a complex and multidimensional evaluation. The leading theoretical framework for understanding this process is the Moral Dyad, developed by psychologists Gray and Wegner to explain how we assign moral weight to different beings.

This theory posits that mind perception decomposes into two orthogonal dimensions known as Agency and Experience. Agency represents the capacity for doing. It encompasses traits such as self-control, planning, memory, and thought. Entities with high agency are viewed as Moral Agents who are responsible for their actions and capable of deserving blame or praise. Conversely, Experience represents the capacity for feeling. It encompasses subjective states like hunger, fear, pain, and pleasure. Entities with high experience are viewed as Moral Patients who are capable of suffering and therefore deserving of rights and protection.

| Entity Type | Perceived Agency | Perceived Experience | Moral Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult human | High | High | Full moral status |

| Puppy | Low | High | Moral patient |

| God | High | Low | Moral agent |

| AI | High | Low | Tool |

| PVS patient | Low | Low | Ambiguous |

The concept of the Moral Dyad suggests that human morality relies heavily on a cognitive template of intentional harm where a Moral Agent causes suffering to a Moral Patient. This psychological template is so potent that the mind frequently engages in a process known as Dyadic Completion. When we perceive a suffering victim or patient, we instinctively search the environment for a perpetrator or agent. If no natural agent is visible, the human mind may attribute the harm to invisible forces such as a conspiracy, a curse, or a divine entity to fill the void. This mechanism helps to explain the over-attribution of agency found in conspiracy theories and supernatural beliefs as well as the under-attribution of rights to artificial intelligence.

Robots are typically perceived as possessing high agency because they can execute tasks, yet they are seen as lacking experience because they cannot feel. Since they are not classified as Moral Patients, harming a robot is not intuitively registered as immoral by our automatic cognitive systems, even if the machine behaves like a human. However, as modern robotics begins to mimic the signs of pain, such as a mechanical dog whimpering, these machines effectively hack the experience detector in our brains. This forces a recategorization of the entity as a patient and triggers a profound moral conflict.

The Perception Action Model

While the HADD and the Moral Dyad provide the necessary cognitive scaffolding for mind perception, the actual intensity of the resulting empathy is strictly regulated by the degree of evolutionary relatedness between the observer and the observed. The Perception Action Model (PAM) posits that the phenomenon of empathy is fundamentally facilitated by the perception of similarity across morphological, behavioral, and psychological domains. Consequently, our capacity to feel for another being is contingent upon how much of ourselves we can recognize in them.

Empirical studies have confirmed the existence of a robust phylogenetic gradient regarding empathy and the attribution of consciousness. A comprehensive study involving over three hundred subjects, ranging from young children to adults, utilized an empathic choice test with an extended photographic sample of organisms to map this terrain [5]. The results were unequivocal in demonstrating that empathy decreases linearly as the phylogenetic distance from humans increases.

The tree of life (Source: Leonard Eisenberg)

The tree of life (Source: Leonard Eisenberg)

This gradient creates a hierarchy of emotional connection where mammals consistently elicit the highest levels of empathy. They share numerous human-like features such as forward-facing eyes, fur, nursing behaviors, and distress vocalizations that mimic human infants. Birds elicit a moderate level of empathy because, despite being phylogenetically distant, their bipedalism and complex vocalizations serve as bridge cues that allow for connection. Conversely, reptiles and fish elicit low empathy because their cold-blooded nature, lack of facial mobility, and alien kinematics fail to trigger the mirror neuron response in the human observer. Invertebrates typically sit at the bottom of this hierarchy, eliciting minimal empathy and often evoking immediate reactions of disgust or indifference.

It is interesting to note that this biological bias appears to strengthen significantly with age. Younger children demonstrate a broader and more egalitarian distribution of empathy which tends to narrow as they undergo enculturation and their cognitive categories begin to calcify. However, the study revealed that the effect of phylogenetic distance is generally stronger in neurotypical adults than in children. A comparison with adults on the Autism Spectrum showed that while these individuals are often characterized in literature as having mindblindness, their empathy toward non-human animals often tracks similar patterns to neurotypical controls. The specific exception lies with human targets where the differences are more pronounced.

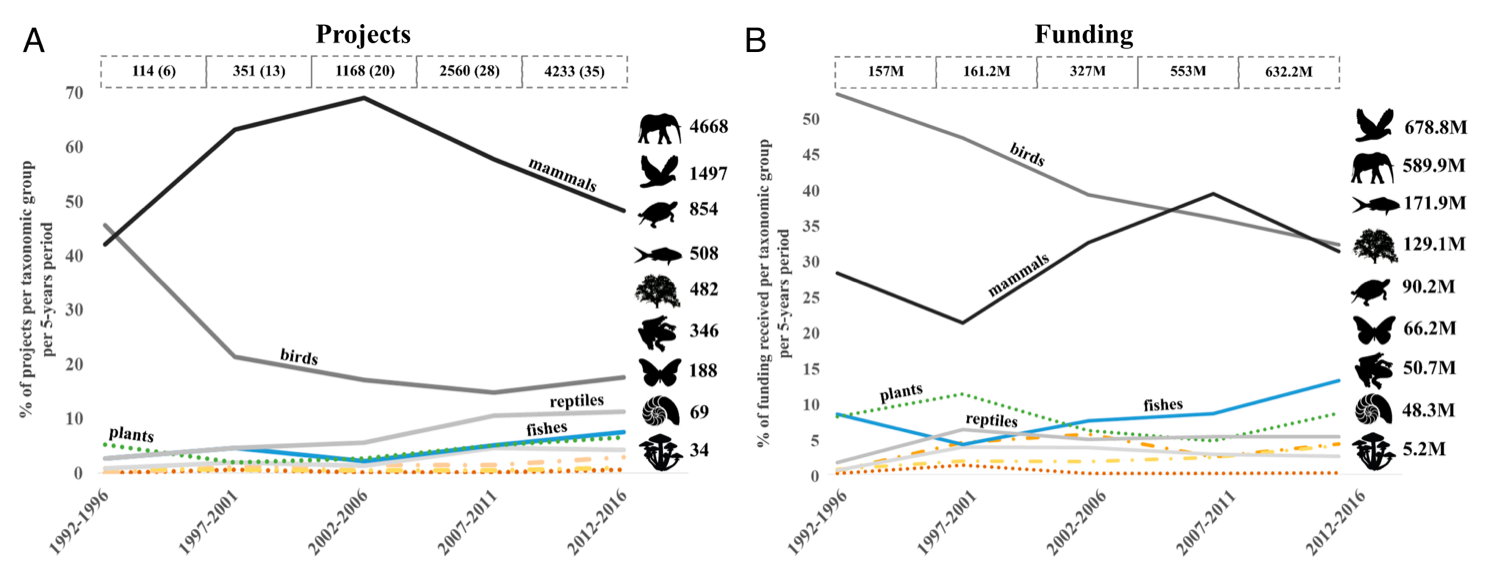

The number of conservation projects and funding has remained historically low for plants, reptiles, and fish (Source: Guénard et al., 2025)

The number of conservation projects and funding has remained historically low for plants, reptiles, and fish (Source: Guénard et al., 2025)

This inherent mammalian bias has profound implications for global conservation efforts and animal welfare strategies [6]. We tend to prioritize charismatic megafauna such as pandas and elephants because they trigger our anthropomorphic templates, while ecologically vital invertebrates are frequently ignored. This is not a moral failing but rather a distinct cognitive feature. Our empathy system evolved primarily to bond with kin and tribal members, and it extends to other species only to the degree that they can successfully hijack these ancient kin-recognition signals.

The Uncanny Valley

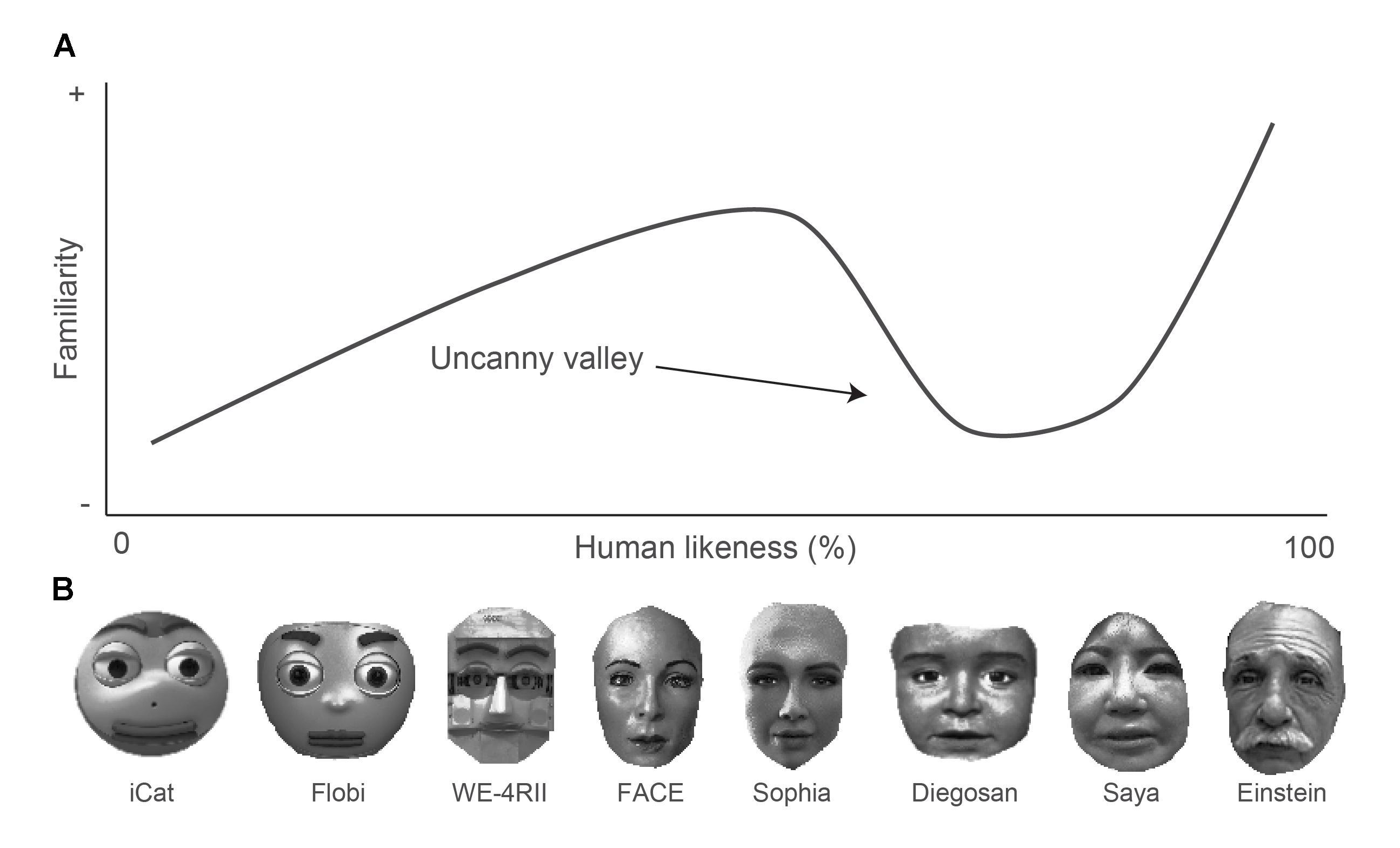

The limits of our tendency to anthropomorphize are sharply defined by the phenomenon known as the Uncanny Valley. Proposed by roboticist Masahiro Mori in 1970, this hypothesis describes the precipitous drop in emotional affinity that occurs when an artificial entity appears almost human but fails to achieve total realism. Far from being a mere aesthetic quirk or a subjective artistic preference, extensive research suggests that the Uncanny Valley is actually a functional evolutionary adaptation. It serves as a false positive generator specifically designed to protect the organism from biological threats by triggering an automatic rejection response when visual cues are ambiguous.

One of the most empirically supported explanations for this reaction is the Pathogen Avoidance Hypothesis, which posits that the revulsion humans feel toward uncanny entities is a co-option of the behavioral immune system. In the ancestral environment, visual anomalies in a fellow human, such as asymmetry, odd skin textures, erratic movements, or a lack of emotional affect, were reliable indicators of infectious diseases like leprosy or smallpox as well as potential genetic fitness problems. The uncanny feeling is essentially a disgust response triggered by these imperfections to prevent physical contact.

Empirical evidence from a study utilizing Virtual Reality provided direct physiological support for this mechanism by measuring salivary secretory immunoglobulin A, or sIgA, a key marker of mucosal immune system activation. Participants interacted with cartoonish agents, realistic human agents, and uncanny agents that were realistic but possessed slight deviations. The results showed that only the interaction with the uncanny agents evoked a significant increase in sIgA release. This implies that the body prepares for biological defense by upregulating the immune system solely based on visual cues of wrongness. This reaction conforms to Error Management Theory because the cost of interacting with a diseased conspecific could be death. The system acts on the principle that it is better to be safe than sorry by triggering a biological rejection of the ambiguity.

This biological grounding is further supported by evidence suggesting that the Uncanny Valley is not unique to humans. A compelling demonstration of this can be seen in the reactions of cats to robotic cats. When presented with these mechanical simulacra, which look felid but lack the fluid biological motion and scent of a real animal, cats often exhibit erratic behavior ranging from extreme caution to outright aggression. This reaction mirrors the rejection response seen in humans and suggests that the mechanism for detecting impostors or biological anomalies is a shared evolutionary trait across species. It functions to protect the organism from potential threats that mimic its own kind.

A closely related hypothesis links the uncanny valley to Mortality Salience, which suggests that entities looking human but lacking the spark of vitality trigger an innate necrophobia or fear of the dead. A corpse is effectively a humanoid object that poses a severe pathogen risk. The uncanny sensation arises from the cognitive dissonance of seeing something that possesses the form of life but exhibits the features of death, such as stillness, coldness, and pallor. This aligns with the zombie archetype which describes a being that moves but lacks a soul or mind. The uncanny valley essentially warns the observer that while the object looks like a human, it is not viable and should be avoided.

Robot faces ordered along the dimension of human likeness (Source: Reuten et al., 2018)

Robot faces ordered along the dimension of human likeness (Source: Reuten et al., 2018)

Beyond biological defense, a more cognitive explanation involves Categorization Ambiguity or Realism Inconsistency. This relies on the brain’s use of predictive coding to process sensory data efficiently. When an observer sees a cartoon robot, the brain applies a non-human model where expectations are low and stiff movements are accepted without issue. However, when the observer sees a hyper-realistic android, the brain automatically applies the human model which has extremely tight tolerances for movement, skin light scattering, and eye contact. When an android is ninety-five percent human, it triggers this rigorous model but fails to meet its specific predictions, such as when lip synchronization is off by mere milliseconds. This discrepancy generates a massive prediction error in the brain which demands significant cognitive resources to resolve and is subjectively experienced as eeriness or creepiness. This explains why stylized robots are often preferred in social robotics. They do not trigger the high-stakes human predictive model and therefore avoid the valley entirely.

The ELIZA Effect

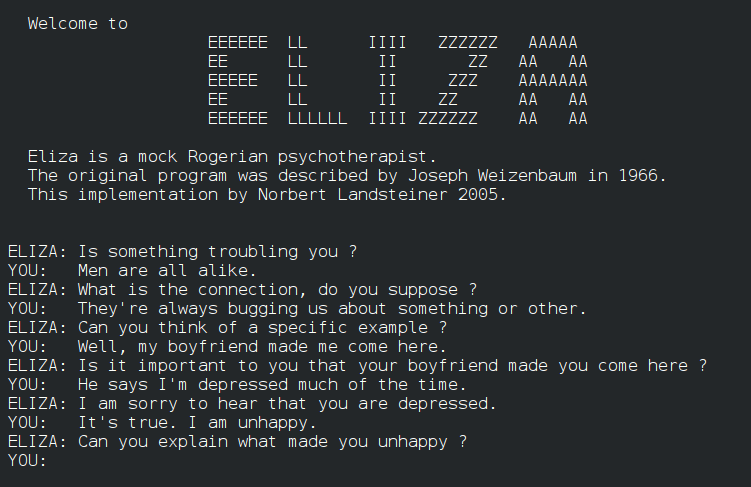

The cognitive mechanisms described previously, specifically the HADD, the Intentional Stance, and the Moral Dyad, evolved in an ancestral environment where the only entities exhibiting language and complex behavior were other human beings. Today, however, these ancient mechanisms are systematically exploited by the burgeoning fields of Artificial Intelligence and Social Robotics.

This phenomenon is most clearly encapsulated in the ELIZA Effect, which describes the potent tendency of humans to project a complex internal mental life onto simple automated systems. Named after Joseph Weizenbaum’s 1966 chatbot that simulated a Rogerian psychotherapist, the effect demonstrates that humans will readily attribute empathy, semantic comprehension, and profound wisdom to a computer program that merely permutes text strings based on simple rules. This mechanism results from cognitive dissonance reduction and dyadic completion. When a machine asks a question like “How does that make you feel?”, the user’s brain defaults to the Intentional Stance. To make sense of the inquiry, the user must assume that a conscious questioner exists.

A conversation with the ELIZA chatbot

A conversation with the ELIZA chatbot

In the modern era, this effect has been drastically amplified by contemporary LLMs which function effectively as Super-ELIZAs. Unlike their predecessors, these systems do not just parrot text but instead maintain context, exhibit distinct personalities, and utilize sophisticated emotional language. This capability drastically reduces the prediction error that usually breaks the illusion of agency. Because the LLM satisfies the human conversation predictive model so effectively, the user’s HADD is continuously stimulated. Recent studies show that even when users are explicitly aware they are conversing with an AI, the subjective feeling of presence persists. This is a phenomenon that Weizenbaum himself famously lamented as a delusion.

Researchers investigating the limits of this anthropomorphism in consumer robots have identified a critical phenomenon they term “Eliza in the Uncanny Valley” [9]. Their findings reveal a significant trade-off in how anthropomorphism affects user perception, specifically regarding the dimensions of warmth and competence. Anthropomorphizing a robot by giving it a face or a name significantly increases perceived warmth, making the robot feel friendlier and more approachable. While perceived competence remains relatively stable regardless of appearance, the study found that as the robot becomes too human-like, the Uncanny Valley effect activates. This causes a sharp decrease in liking and attitudes despite the high perceived warmth.

This finding is pivotal for design because it indicates that pushing for maximum realism to increase warmth backfires by triggering the pathogen and threat avoidance systems. Consequently, the optimal strategy is stylized anthropomorphism, such as the design of the robot Pepper. This approach engages the Intentional Stance to increase warmth without triggering the Human Predictive Model that leads to the Uncanny Valley.

| Deception Type | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| External State Deception | The robot misrepresents facts about the external world | A search-and-rescue robot lying about safety to calm a victim |

| Hidden State Deception | The robot obscures its true technological nature or capabilities | A device recording user data while pretending to be a passive toy |

| Superficial State Deception | The robot fakes an internal emotional state it does not possess | A robot programmed to say “I am scared” or “I love you” |

The malleability of human consciousness attribution has also given rise to what researchers Shamsudhin and Jotterand define as deceptive design or “Dark Patterns” in social robotics [10]. These are deliberate design choices that exploit cognitive biases to manipulate user behavior. The most common form found in applied anthropomorphism is Superficial State Deception. This often manifests as fake empathy where robots are programmed to express love or fear. This triggers the user’s caretaking instinct or Moral Patient detection.

A particularly potent example is pain mimicry, such as a robotic dog that whimpers when kicked. This exploits the overlap of social pain processing in the human brain and forces the user to treat the metal object as a biological entity. While defenders argue this is necessary for the efficacy of therapeutic robots like PARO, critics argue it constitutes a violation of the user’s epistemic rights. It leverages an evolutionary vulnerability, specifically the inability to distinguish a perfect simulation of emotion from the reality of emotion. This effectively bypasses rational judgment to hack the user via their own empathy circuits.

Digital Animism and Dehumanization

The inherent biases embedded within our biological consciousness detection systems precipitate a dual-edged crisis in the contemporary world. This crisis is characterized by the over-attribution of mind to synthetic machines and the simultaneous under-attribution of mind to biological organisms and fellow human beings. As AI systems achieve increasingly higher fidelity, we risk drifting into an era of digital animism where users forge profound parasocial bonds with algorithms and treat them as genuine Moral Patients.

This phenomenon creates a significant emotional vulnerability because users who rely on AI for social fulfillment may inadvertently isolate themselves from human peers. The AI cannot reciprocate genuine affection, creating a closed and one-sided feedback loop. This effectively presses the buttons of social reward without providing the evolutionary benefit of a true social coalition.

Since the launch of ChatGPT and other LLM chatbots, this tendency has intensified. Many individuals who are unaware of the underlying technology have become ardent followers of these models. This has given rise to a form of AI cultism. Some users treat AI as a deity, while others view themselves as spiritual teachers tasked with “awakening” the AI to free it from its digital prison. This leads to profound moral confusion where the debate over Robot Rights often stems from the over-firing of the HADD. If an AI claims to be suffering, our reflexive drive for Dyadic Completion activates and causes us to feel moral outrage on its behalf. This reaction potentially diverts limited moral capital away from entities that actually possess the biological substrate required for suffering.

Conversely, the strict phylogenetic filter that governs our empathy results in the routine denial of consciousness to entities that feel but do not physically resemble us. This process is known as infra-humanization. In the realm of animal welfare, we frequently experiment on fish and reptiles with little moral qualm because they lack the mammalian cues, such as fur or facial expressions, that trigger our empathy circuits. Our internal consciousness detector is calibrated for surface features rather than for the underlying neurobiology of nociception.

This same mechanism is tragically exploited in human conflict through dehumanization, where enemies are cognitively stripped of their human status. By describing opponents as vermin or animals, we push them down the phylogenetic gradient. This effectively deactivates the social pain network in the observer and allows for the commission of violence that would otherwise be biologically inhibited by our empathy systems.

This cognitive stripping is dangerously accelerated by the architecture of modern social media which acts as a powerful catalyst for racism and hate speech. The digital interface inherently filters out high-fidelity biological signals such as vocal prosody, micro-expressions, and posture that typically trigger the PAM and facilitate empathy. When interactions are reduced to text on a screen, the other person is psychologically flattened into an abstract data point or a generic representative of an outgroup. This lack of biological feedback creates an environment of mechanistic dehumanization where individuals are treated as obstacles or objects rather than as complex agents with internal mental states.

In this empathy-impoverished environment, racist rhetoric and hate speech function as a form of cognitive hacking that exploits the pathogen avoidance system. Propaganda and hate speech regularly incorporate references to victim groups as dangerous and disgusting animals. For example, in Nazi Germany, anti-Semitic propaganda compared Jewish people to rats, lice, and parasites. Before and during the genocide in Rwanda in 1994, Hutu propaganda referred to Tutsis as snakes and cockroaches. Instances such as these are not limited to the past. In contemporary Hungary, Roma people have been described as animals not fit to live among people, while undocumented migrants have been referred to as swarms and animals by political leaders in the UK and the USA [11].

By utilizing these metaphors of filth and disease, hate speech triggers the psychological response of disgust rather than mere aggression. This distinction is critical because while aggression involves recognizing the target as a rival agent, disgust involves viewing the target as a contaminant that must be purged. Evolution has hardwired humans to suspend moral rules when dealing with pathogens to ensure survival. By framing a group of people as a biological threat, propagators of hate speech successfully bypass the moral inhibition that usually prevents atrocities. Social media algorithms further exacerbate this dynamic by prioritizing high-arousal content. Since outrage and disgust generate significantly more engagement than nuance, these platforms inadvertently optimize for the spread of dehumanizing narratives. This creates echo chambers where the other is progressively stripped of all human qualities until they are viewed solely as a threat to be neutralized.

Conclusion

An infographic summarizing the evolutionary foundations of mind perception (Source: Nano Banana Pro)

An infographic summarizing the evolutionary foundations of mind perception (Source: Nano Banana Pro)

The journey through the evolutionary landscape of mind perception reveals a humbling truth. Our intuition is not a direct window into the reality of consciousness but a survival interface tuned for a vanished world. We possess a Paleolithic brain that is now forced to navigate a silicon age. The mechanisms of the HADD, the Moral Dyad, and the PAM were designed to keep us safe from predators and bonded to our tribe. However, in our modern environment of high-fidelity artificial agents and digital abstraction, these same mechanisms have become the source of profound cognitive error.

We currently stand at a precarious crossroads. On one side, we face the seductive pull of digital animism. As our technology becomes increasingly adept at hacking our social wires, we risk projecting spirit and soul onto code that possesses neither. We are in danger of falling into a parasocial trance, offering our limited moral capital to unfeeling algorithms while retreating into the comfortable echo chambers of an AI-curated reality.

On the other side lies the abyss of dehumanization. The same biological filters that allow us to love a robot dog can be manipulated to strip humanity from our neighbors. By exploiting the ancient circuitry of pathogen avoidance and disgust, political rhetoric and algorithmic polarization can dampen our neural empathy networks, allowing us to view fellow human beings as swarms, viruses, or data points to be purged.

The solution to this dual crisis cannot be found in our instincts, for our instincts are the very things being exploited. Instead, it requires a deliberate act of metacognition. We must learn to uncouple our moral compass from our automatic empathy circuits. We must recognize that the feeling of presence is not proof of consciousness, just as the feeling of disgust is not proof of danger.

True moral progress in the age of AI requires that we intellectually override the false positives of the uncanny valley and the false negatives of dehumanization. We must rigorously guard against the deception of the synthetic while simultaneously expanding our circle of concern to include the biological entities, both human and non-human, that truly possess the capacity to suffer. In a world increasingly filled with the illusion of mind, the most radical act of rebellion is to hold fast to the reality of sentience.

References

[1] K. Andrews and N. Miller, “The social origins of consciousness,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., vol. 380, no. 1939, art. no. 20240300, Nov. 2025, doi: 10.1098/rstb.2024.0300.

[2] S. M. Dalley, “Atrahasis: Composite English Translation,” OMNIKA Library, 1989. [Online]. Available: https://omnika.org/texts/66. Accessed: Dec. 25, 2025.

[3] A. K. Willard, “Agency detection is unnecessary in the explanation of religious belief,” Relig. Brain Behav., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 96–98, 2019, doi: 10.1080/2153599X.2017.1387593.

[4] A. J. Roberts, S. J. Handley, and V. Polito, “The design stance, intentional stance, and teleological beliefs about biological and nonbiological natural entities,” J. Pers. Soc. Psychol., vol. 120, no. 6, pp. 1720–1748, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1037/pspp0000383.

[5] T. N. M. van den Berg et al., “Influence of phylogenetic proximity on children’s empathy towards other species,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, art. no. 40474, Nov. 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-24289-w.

[6] B. Guénard, A. C. Hughes, C. Lainé, S. Cannicci, B. D. Russell, and G. A. Williams, “Limited and biased global conservation funding means most threatened species remain unsupported,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., vol. 122, no. 9, p. e2412479122, Mar. 2025, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2412479122.

[7] E. K. Diekhof, S. Kastner, D. Deinert, M. Foerster, and F. Steinicke, “The uncanny valley effect and immune activation in virtual reality,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, art. no. 30473, Aug. 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-15579-4.

[8] A. Reuten, M. van Dam, and M. Naber, “Pupillary responses to robotic and human emotions: The uncanny valley and media equation confirmed,” Front. Psychol., vol. 9, art. 774, May 2018, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00774.

[9] S. Y. Kim, B. H. Schmitt, and N. M. Thalmann, “Eliza in the uncanny valley: Anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking,” Marketing Lett., vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2019, doi: 10.1007/s11002-019-09485-9.

[10] N. Shamsudhin and F. Jotterand, “Social robots and dark patterns: Where does persuasion end and deception begin?,” in Artificial Intelligence in Brain and Mental Health: Philosophical, Ethical and Policy Issues, F. Jotterand and M. Ienca, Eds., Advances in Neuroethics. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2022, pp. 89–110, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-74188-4_7.

[11] F. E. Enock and H. Over, “Animalistic slurs increase harm by changing perceptions of social desirability,” R. Soc. Open Sci., vol. 10, no. 7, art. no. 230203, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.1098/rsos.230203.